Date: January 21, 2026, Tags: #CyberSecurity #Cloudflare #ACME #SSL #ZeroDay #DevOps

In the last decade, the web moved almost exclusively to HTTPS. This massive shift wasn’t powered by manual effort, but by automation. The unsung hero of an encrypted web is the ACME Protocol, the engine that powers Let’s Encrypt and many other modern Certificate Authorities (CAs).

However, as a recent critical disclosure from Cloudflare highlights, the very mechanisms designed to make security easier can sometimes create unexpected backdoors.

This week, news broke detailing a now-patched zero-day vulnerability in Cloudflare’s infrastructure where the rules designed to allow ACME traffic accidentally bypassed their entire Web Application Firewall (WAF).

In this post, we’re going deep. We will look at how the ACME protocol actually works under the hood, understand its validation challenges, and then dissect how attackers nearly turned that automation against one of the world’s largest security providers.

Part 1: The Foundation – What is the ACME Protocol?

Before we get to the exploit, we need to understand the machinery.

ACME (Automated Certificate Management Environment), defined in IETF RFC 8555, is a protocol designed to automate the interaction between a Certificate Authority and a user’s web server.

Before ACME, getting an SSL certificate was a pain: generate a CSR, email it to a vendor, wait for a phone call to verify who you were, receive a file, upload it, and configure Apache/Nginx. Then, repeat the process every year.

ACME turned that manual week-long process into a 10-second automated script.

The Architecture

ACME is a client-server dialogue spoken in JSON over HTTPS.

- The Client: Software on your server (like Certbot, acme.sh, or Caddy).

- The Server (CA): The entity issuing the certificate (like Let’s Encrypt, ZeroSSL).

Every message sent by the client is cryptographically signed with a private account key, ensuring the CA knows exactly who is making the request.

The Lifecycle in Brief

- Account Setup: The client generates a key pair and registers with the CA.

- Order: The client tells the CA, “I want a certificate for

example.com.” - Challenges (The Crucial Part): The CA says, “Prove you own that domain by completing these tasks.”

- Finalization: Once proved, the client sends a Certificate Signing Request (CSR).

- Issuance: The CA sends back the signed certificate.

Part 2: Proving Ownership – The ACME Validation Challenges

The heart of the ACME protocol—and the root of the Cloudflare vulnerability—lies in Phase 3: Challenges.

How does a remote CA automatically know you control a domain? It asks your server to perform a task that only the domain owner could theoretically achieve. There are three main types defined today:

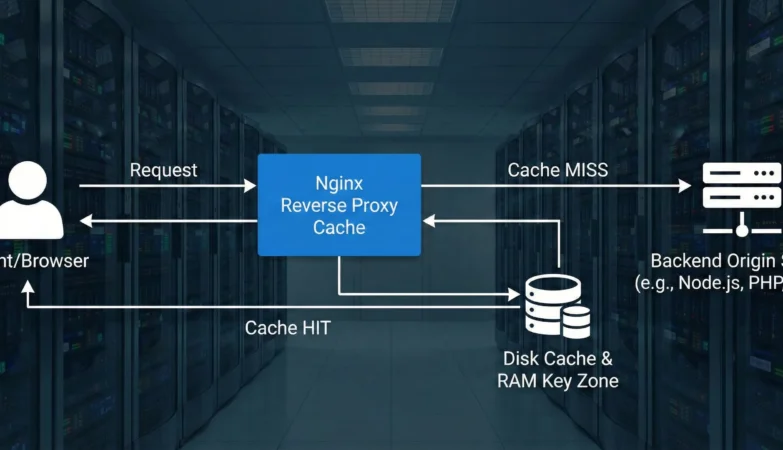

1. HTTP-01 (The Standard, and the Vector)

This is the most common method.

- The CA’s Challenge: “If you own this server, place this specific cryptographic token into a file at a very specific path.”

- The Path:

http://yourdomain.com/.well-known/acme-challenge/<token> - Verification: The CA makes a standard HTTP GET request to that URL from multiple vantage points around the internet. If it sees the correct token, you pass.

2. DNS-01 (The Power User Method)

- The CA’s Challenge: “Place this token into a DNS TXT record for your domain.”

- Verification: The CA queries global DNS servers.

- Use Case: This is required for Wildcard Certificates (

*.example.com) or for servers that are behind firewalls and not reachable over the public internet on port 80.

3. TLS-ALPN-01 (The Modern Method)

This method performs the validation during the initial TLS handshake on port 443, using a special self-signed certificate containing the challenge data. It’s fast and avoids port 80, but is harder to implement manually.

Part 3: The Conflict – WAFs vs. Automation

Now we have the context for the exploit disclosed this week.

Imagine you are Cloudflare. You sit in front of millions of websites, providing a Web Application Firewall (WAF) that blocks malicious bots, SQL injection attempts, and vulnerability scanners.

Your WAF rules are generally suspicious of odd automated traffic.

However, millions of your customers use Let’s Encrypt. Every 60 days, the Let’s Encrypt bots must hit your customers’ origin servers on the /.well-known/acme-challenge/ path to renew certificates (using the HTTP-01 method defined above).

If your WAF blocks those requests because they look like “bot traffic,” your customers’ SSL certificates expire, their sites go down, and they blame you.

The Tension: You need strong security rules, but you must create an exception for ACME validation traffic.

Part 4: The “Universal Bypass” Zero-Day

The vulnerability, discovered by security researchers at FearsOff and disclosed on January 19, 2026, lay in how Cloudflare implemented that exception.

The Flawed Logic

To ensure customer certificates didn’t break, Cloudflare implemented a global rule at their network edge. In simple terms, the logic went something like this:

If an incoming HTTP request starts with the path

/.well-known/acme-challenge/, assume it is a legitimate certificate validation attempt and bypass the WAF to let it through to the origin server.

The intention was good: prioritize SSL reliability. The execution, however, was flawed.

The Attack Mechanism

Attackers realized that this “allowlist” was static. The system wasn’t checking if the request was actually from Let’s Encrypt, nor was it checking if the traffic was only a validation token. It just looked at the beginning of the URL path.

An attacker could take a malicious payload that would normally be blocked by the WAF and append it to the “magic path.”

Normal Attack (Blocked):

HTTP

GET /wp-login.php?cmd=malicious_code HTTP/1.1

Host: target-website.com

Result: The Cloudflare WAF sees a known attack signature and blocks it. 🛑

The Zero-Day Attack (Bypassed):

HTTP

GET /.well-known/acme-challenge/any_text_here?cmd=malicious_code HTTP/1.1

Host: target-website.com

Result: The edge network sees the magic ACME path. It disables the WAF for this request. The request—malicious payload included—is forwarded directly to the origin server. ✅

If the origin server had an underlying vulnerability that Cloudflare was supposed to be shielding, the attacker could now exploit it at will.

Part 5: The Fix and Lessons Learned

Cloudflare patched this vulnerability late in 2025 before the full disclosure. The fix required moving from a static allowance to a dynamic check.

Instead of blindly allowing anything on that path, the Cloudflare edge now performs a real-time check:

- Is the request destined for the ACME challenge path?

- Crucially: Is there currently an active, pending ACME order underway for this specific hostname managed by Cloudflare?

If there is no active certificate order, there is no reason for that path to be accessed, and the WAF rules remain active.

The Takeaway

The ACME protocol itself was not broken here; it functioned exactly as designed in RFC 8555.

The failure was in the implementation gap between security tooling and automation protocols. In an attempt to make automation frictionless, security controls were loosened too much.

For DevOps and Security engineers, this serves as a potent reminder: every exception you create in a firewall—no matter how well-intentioned—is a potential doorway waiting to be pried open. Whitelists should never be static; they must always verify context.

External Resorces

https://fearsoff.org/research/cloudflare-acme

https://cybersecuritynews.com/cloudflare-zero-day-vulnerability/